DUMP is an object-initiated enquiry taking as a starting point the first official Australian colonial currency: Lachlan Macquarie’s holey dollar and dump of 1812. Dump biomaps at a molecular level the silver of the holey dollar, through a linked series of anthropogenic landscapes, from Spanish colonial silver mines to Broken Hill and on to the Antarctic.

Artist statement: here

Matter in circulation

Catalogue essay by Anneke Jaspers, curator, Contemporary Art, Art Gallery of NSW

Two coins appear in Penelope Cain’s installation Money Tree (2018), enlarged and adorned in the style of regalia. This money – Australia’s first ‘official’ currency – entered circulation in 1813 at the behest of Governor Lachlan Macquarie.

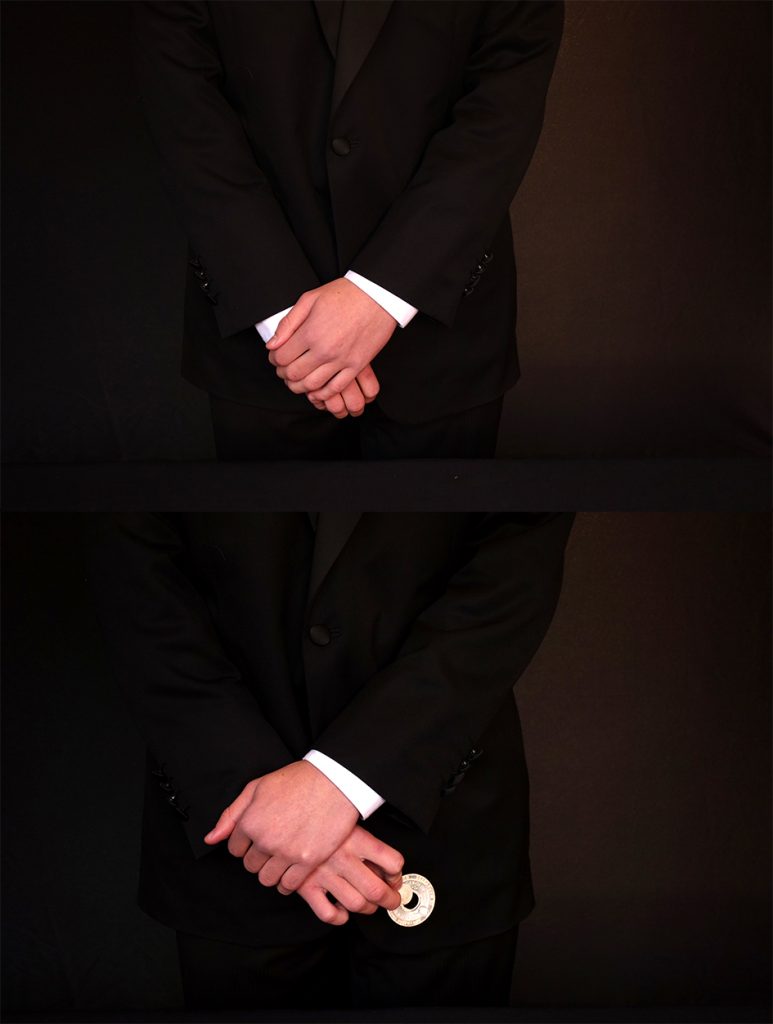

The silver was sourced all the way from South America in the form of Spanish dollars. Famously, Macquarie re-minted the coins in Sydney, extracting a smaller disc from the middle of each dollar to double the volume of local currency. From here, they dispersed throughout the colony: talismanic objects, traded between thousands of hands, tracing a complex history of movement and commerce.

The circular void in the centre of Macquarie’s ‘holey dollar’ has a certain metaphoric charge. It conjures the larger process of geological displacement that yielded the money’s raw material. And it alludes to the abstraction of economic value from this material base. Value, Cain’s exhibition reminds us, is always culturally determined. Macquarie introduced the dollar into a context that had a highly evolved economy of exchange dating back millennia, just with different kinds of currencies. Shells and pituri were more precious than metal.

The bi-lingual inscriptions on the holey dollar, along with the crown stamped on the inner ‘dump’, reflect the symbolic power of coins, like flags, as markers of sovereignty. In this spirit, the totemic form of Money Tree (2018) echoes the upright markers of The Pale Colour of Shadows on the Mid-Summer Snow (2018), on which we glimpse a restless image of Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen laying claim to the South Pole in 1911. This iconic moment – which spurred Antarctica’s transition from land into territory – points to a larger truth about imperialism. Economic and political power are intrinsically linked. Ore for Macquarie’s dollars was mined from Cerro Rico de Potosí, the world’s largest known silver deposit. Potosí is now located in Bolivia; however, when Spanish colonists began extraction in the sixteenth century, it was part of Peru. These shifting claims to land are incidental to the geology they inscribe, which has an infinitely older provenance. The metallurgical lode at Potosí formed more than 13 million years ago. In Australia, similar ore at Broken Hill is dated to 1,800 million years old. Mining operations were established there in 1883: the fateful origin of multinational resource giant BHP.

Historically, dust from the two mines entered the weather system. Ungrounded, these particles were carried thousands of kilometers by what are known – aptly, almost uncannily so – as the global trade winds. Lead disturbed by the silver mining process in Potosí during the 17th and 18th centuries has been found in the Quelccaya glacier in the Andes, while traces from Broken Hill travelled as far as Antarctica in the late 1800s. Ice, it turns out, is an ideal material from which to excavate social history.

These particles find other places to settle. In Broken Hill, lead has found its way into bodies of all kinds, absorbed into the cells of residents, vegetation and fauna. The local bee population carries this lead around the landscape on its daily search for pollen. Here, trapped within their tiny biological systems, it becomes inadvertently subject to another economy of molecular distribution and transformation. In this strange way, the lead remains airborne. Bees also live in colonies. As Cain observes in her video Dust for the Antarctic (2018), these colonies have social structures that effect the distribution of trace elements from the pollen harvesting process. The aristocracy is protected from exposure, while the worker bees accumulate lead at far higher levels. The burden of toxicity is distributed along class lines: a situation replicated in the human realm, historically and now, in mining and many other industries. Bodies are also inscribed with value.

These days, the intense mobility of mine workers is notorious, amplified by the economic forces of neoliberal globalisation. But the fly-in-fly-out phenomenon has a long lineage. The man who first struck silver at Broken Hill, Charles Rasp, was himself a labour migrant: a boundary rider turned prospector, whose good fortune enabled him to transcend his social class. As a symbol of his new wealth, Rasp acquired an ornamental table decoration made from smelted tea sets combined with market silver, some of which likely originated in Peru. This sculpture, which long outlived Rasp, is depicted in Cain’s work The Silver Tree (2018), where its elaborate detail reveals a naïve, nationalistic sentiment. Kangaroos and emus gather at the base of a large tree, alongside two Aboriginal figures and a drover. The tree is not native. Like the rest of the scene, it is a European fantasy: an ideological projection of one landscape into another, just as its base material has also been transposed from the opposite side of the world.

July 2018

Dust for the Antarctic, digital video with sound, 2018

Supply Side Magical Thinking Digital video, no sound

This exhibition was held at 24 July- 11 Aug 2018,

Kudos Gallery , 6 Napier St, Paddington,

NSW 2021

The artist wishes to acknowledge:

With thanks to the Albert Kersten Mining and Minerals Museum, Broken Hill, for providing access to photograph the Silver Tree.

Acknowledgement is made to the Kaurna people and lands in which the Silver Tree was made and the Wiljakali people and lands in which the Silver Tree is now located.

With thanks to MAAS for providing access to the holey dollars and dumps held in its vast collection.

With thanks to the National Library, for access to the image from ‘The Successful Explorers at the South Pole, 14th December 1911 [picture]/ Olav Bjaaland’.

With thanks to Dave and Carol Apiarists for their knowledge and generous access to film.

Many thanks to the dedicated team at the Broken Hill Artist Exchange

REFERENCES:

Identifying Sources of Environmental Contamination in European Honey Bees (Apis mellifera) Using Trace Elements and Lead Isotopic Compositions

Xiaoteng Zhou† , Mark Patrick Taylor*†‡ , Peter J. Davies†‡, and Shiva Prasad§

Fingerprinting sources of environmental contamination using European honeybees

X ZHOU1, MP TAYLOR1, PJ DAVIES1, C DONG1, 2017.

The Association between Environmental Lead Exposure and High School Educational Outcomes in Four Communities in New South Wales, Australia, 2017

Jennifer McCrindle 1,*, Donna Green 2 and Marianne Sullivan 3

BLACK BLUEBUSH AND OLD MAN SALTBUSH BIOGEOCHEMISTRY ON A CONTAMINATED SITE: BROKEN HILL, NEW SOUTH WALES, AUSTRALIA

Christina Low1, Damian Gore1, Mark Patrick Taylor1& Honway Louie

Antarctic-wide array of high-resolution ice core records reveals pervasive lead pollution began in 1889 and persists today. Joseph R Mcconnell et al. Scientific Reports · July 2014

Mercury pollution from the past mining of gold and silver in the Americas.

Jerome O. Nriagu

The death of honey bees and environmental pollution by pesticides: The honey bees as biological indicators.

Laura Bortolotti et al. Bulletin of Insectology · January 2003